I thought a description of my own change of attitudes about this metamorphosis might be helpful to those not as involved in the process.

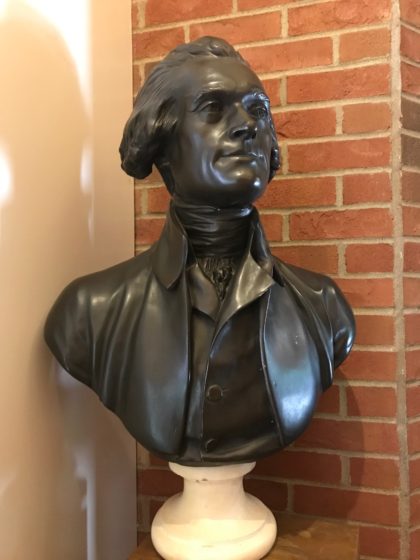

FAREWELL, “THOMAS JEFFERSON”

When I first heard the proposal to change our church’s name, my knee-jerk response was to dig in my heels and defend everything I loved about our old name. It seemed appropriate that Thomas Jefferson held Unitarian views, was an important figure in American history, and inspired the name of our location in Jefferson County. Most of all, I associated many years of fond experiences and many lifelong friendships with the TJ identity.

In childhood, I revered Jefferson. A family trip to his Monticello estate inspired me. I wanted to emulate this man who designed beautiful buildings, invented clever devices, played musical instruments, studied natural history, experimented with new crops, organized expeditions, founded a University and established the Library of Congress. In third grade, I dressed up in a wig fashioned from scotch tape and cotton balls to portray my hero in our very patriotic school play. My tiny voice swelled dramatically as my character declared it “necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them to another.”

As an adult who joined a faith community decidedly outside of Kentucky’s cultural mainstream, I leaned on the Jefferson identity as affirmation of “normal” American values. How evil could these Unitarians be, my fundamentalist relatives thought, if their church is named after one of our Founding Fathers? Even after acquiring a more mature understanding of Jefferson’s flaws, and in spite of unfolding evidence of his behavior as a slaveholder, the easy (and privileged) response was to make excuses. “Jefferson was a product of his time, and shouldn’t be held to a 21st Century standard,” I tried to convince myself.

But this church never let me off the hook. In messages from the pulpit, in the diverse vantage points of guest speakers, in readings of unvarnished history, and in countless conversations with church members, the hard truth was unavoidable. Our namesake’s amazing accomplishments were only possible because he stood on the backs of human beings who were abused in their own time, and then were expunged by history. Jefferson may have been blinded, and was certainly shielded by his position as a prosperous white male in eighteenth century Virginia. We have no such excuse. In time, I came to understand the pain I was inflicting on others by clinging to a tarnished icon of an inhumane era.

Even after the congregation agreed to change its name, the long, methodical selection of a new identity demanded that we all bring our best selves to the table. I doubt that Thomas Jefferson’s own stress while sweating out drafts of our nation’s founding documents could have been much worse than a zoom session with a hundred opinionated Unitarians seeking consensus within the arcane strictures of Robert’s Rules. It was difficult, but worthwhile, to practice letting go of my favorite ideas–trusting that our collective decisions were ultimately wiser than any choices I would have made on my own.

I admit our final selection, “All Peoples,” did seem a bit awkward to me at first. Why not “All People,” or the possessive form, “All People’s” with an apostrophe? Then my biology training kicked in, and the lightbulb clicked on. “Peoples” means a lot more than “People,” because it includes the entire spectrum of human diversity that our church has been striving to serve. In biology, the word “fish” can be plural, but does not imply variety. If I say I went to Kentucky Lake and caught ten fish, they may have all been one kind, like ten bluegill sunfish. However, if I say “fishes,” I’m talking about many species of fish. A book on the fishes of Kentucky would include all the finny forms that swim in our waters.

For the same reason, “All Peoples” denotes every racial, ethnic, religious, gender, age or other category of humankind imaginable. When Thomas Jefferson referred to the “people” in the line I memorized from his Declaration, he meant only one kind of person: white, male, Christian, property owners of American allegiance and West European ancestry. By adopting “All Peoples,” we can transcend Jefferson’s world view and signify our commitment to universal fellowship and genuine inclusion. Changing our name does better communicate that intention, but perhaps even more important are the lessons we’ve learned along the way about letting go of the old, fostering empathy, trusting each other, and embracing a better version of ourselves.

Rob Kingsolver, 12/21/2020